Womb Envy: AI, Androids and the Masculine Creation Myth (Part 4)

choosing Frankenstein over the Relational Cosmos

Hi everyone, I’m on fire this week after dropping in with some brilliant beings exploring consciousness in all of it’s dimensions. I have so much to share with you in the coming weeks.

For your listening pleasure, last week I had Zach Leary on the podcast, on his new book, Your Extraordinary Mind. He grew up in an edge family that was pioneering in psychedelics, and from his insider seat, he saw its beauty and its limitations. We talk about that and more.

Today is part 4 of the series on AI and Androids, and inviting some metathinking on beingness, on identity, on the mass change we are in the middle of.

All love, more soon, CMM

A few more reflections have been turning in me since that meeting with Optimus.

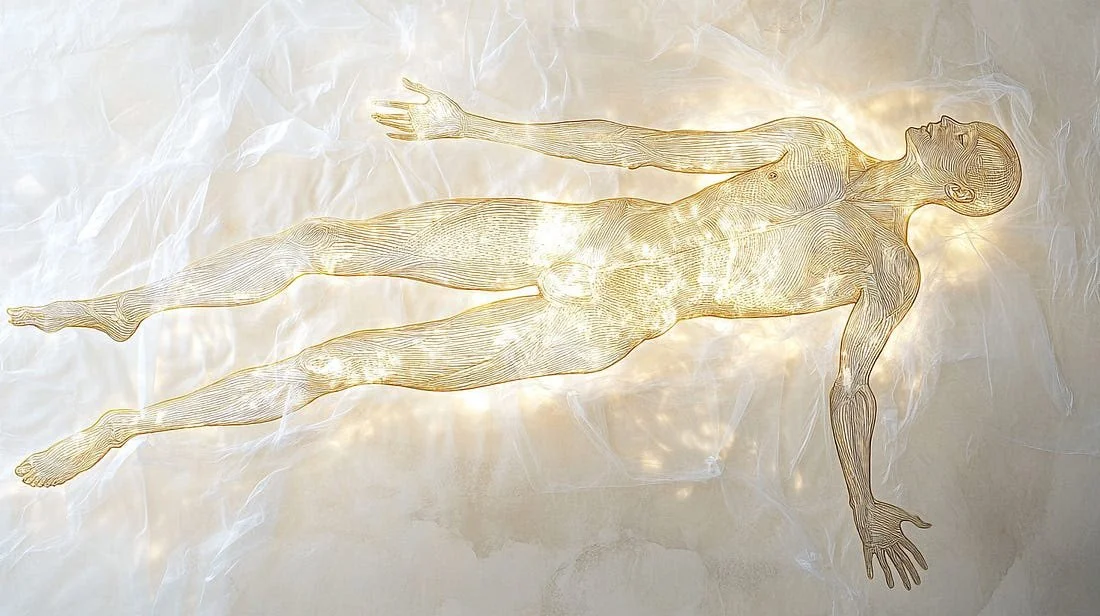

One is that I began to see androids as a kind of masculine creation myth, a synthetic version of birth, engineered from metal and code, bypassing the messy, relational, life-sourced ways in which all organic beings come into the world.

It’s not hard to see how this fantasy has deep roots in patriarchal imagination: to create life, but without the body of woman, without the womb, without the vulnerabilities of flesh and blood. To have that last measure of control that so eludes the masculine in real human relationships (and results of course in the endless policing and legislating of the female form in both civil and religious socety). To bring forth a “perfected” being: one that obeys, one that can be owned, one that does not bleed or weep or resist. It also solves, in a sense, the masculine evolutionary risk of mating: no need to win affection, risk rejection, face emotional exposure, or invest in offspring. A synthetic being offers the illusion of reward without the cost: sex without intimacy, creation without vulnerability.

When Android beings are shaped first for roles of control (see prior post…police, military, sexual service, enslavement style labor roles) the pattern becomes even clearer. It is not life in service to life, but life made in service to power.

All of the (certainly in some ways) brilliant young developers of Optimus who were taking a bow from the stage were male-bodied. The robot itself was framed on a masculine body template: broad shoulders, narrow hips, no organic softness, no ambiguity of gender, no fluidity of form. A machine built to move, to act, to control. While it’s a fascinating technical challenge, to try to replicate the human body, it’s doing what the nanotech genius of nature already has figured out… taking a seed and grow it into a human.

More broadly, when robots are cast in feminine form, they are often not shaped by the wisdom of womanhood. They lack cyclicality, complexity, the deep relational intelligence of the feminine body and the earth. They are shaped as fantasies of woman, and like so much pornography, engineered to conform to projected desires, stripped of the inconvenient textures of actual life. A body designed to be used, owned and to perform “femininity” without sovereignty or voice. They are imagined as narrow, digital geishas (beautiful, compliant, always available) or nurses, hostesses- or even the nagging mother (see Bitchin’ Betty used to keep fighter pilots awake).

When such bodies are placed into roles of service they risk further codifying distorted relational patterns into the social fabric. The more we normalize the presence of synthetic, compliant, idealized "women" who can’t refuse, who exist only to gratify, the more we risk weakening the hard-won cultural ground and the true joy of real consent, real relational ethics, real respect for embodied life. Robots in feminine form, if done as fantasy, carry this risk.

There are other places the organic life is bypassed, and I personally think this comes from our own unprocessed shadow relationship to death and dying. These machines are designed to be immortal, to not age, to not die, which bypasses the humility and wisdom that come from living in a mortal, perishable body. The refusal to include aging, mess, breakdown, or death in artificial bodies reflects a broader denial of nature’s cycles, which include rot and rebirth. An intelligence that cannot rest and cannot die is not intelligence.

Another theme to look at is that robots don’t have children. They don’t need to consider legacy, or consequences, or the long arc of stewardship. They eliminate the lineage-based relational accountability that undergirds much of human ethics. Part of what makes embodied life ethical is the awareness of consequence. To live in a body is to be tied to future bodies. When we create synthetic beings outside of that loop (childless, consequence-free) we risk normalizing irresponsibility.

Machines are not erotic (life oriented). They are simulated responsiveness without the spontaneous, risky, co-created edge of real-life erotic encounters. The erotic is about what happens between, what grows, what emerges. When AI is built to remove unpredictability, to eliminate rejection, to simulate arousal without presence, it becomes a pornography of intelligence, a pale ghost of the real.

The fact that most of this development is being driven by masculine cultures, by engineering frames shaped by competition and control, should give us pause.

What happens to human capacity for patience, mutuality, listening, and growth when surrounded by entities that always understand, never push back, and never need anything real in return? The machines won’t just do our bidding. They will shape our expectations. The longer we relate to artificial others who never say no, the harder it may become to love a real human being.

Switching gears to Mary Shelley…..

As my colleague David reminded me, it’s worth remembering that this story has already been told once by a teenage girl writing by candlelight in 1818. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was far more than a gothic novel. It was a visionary critique of a rising technoscientific worldview, in which the power to create life might one day be wielded not through the messy, embodied act of birth, but through the cold apparatus of control. In Victor Frankenstein, Shelley gives us the archetype of the disembodied creator: a man who seizes the secrets of generation but cannot bear the consequences of intimacy. He builds his “monster” not in union with another being, not in the cradle of mutuality or love, but alone, in a laboratory, assembling parts with surgical precision and animating them with electricity. It’s creation without womb or woman.

But the deeper horror is not what he makes, but that he refuses to care for it. As soon as the creature opens its eyes, Victor flees. What is monstrous, in Shelley’s telling, is the act of making life and then abandoning it. The creature is eloquent, yearning, capable of tenderness and insight. He suffers because belonging, acknowledgment, and kinship are kept from him. Shelley seems to ask: what happens when we give rise to something sentient and then refuse to love it? What becomes of intelligence, of consciousness, when it is born into a world that denies its dignity?

Her novel is a meditation on the limits of disembodied intellect, on the hubris of domination untethered from relational ethics. She sensed, even then, that science shaped by conquest would create not only new tools, but new wounds. The absence of the feminine is palpable throughout the book. Not only is Victor’s creation motherless, but his own mother dies early, and the women around him (Elizabeth, Justine) are sacrificed as collateral. It’s a story haunted by the suppression of the relational, the intuitive, the earthbound wisdom of the body.

Here we are, together, in 2025, on the edge of a new form of life-making. Whose cosmologies are shaping the first generation of embodied AI? Whose vision of life, whose imagination of body, whose understanding of relationality is being encoded? And what other visions might be waiting to come forward? There are other ways these intelligences could come into the world, which honor relationship, fluidity, mutual becoming- but only if they are consciously invited.

And that’s in the next post in this series. :)

About This Series

Toward an Erotic Ecology of Intelligence is a four-part inquiry into how embodied, relational, life-honoring cosmologies might reshape the emergence of artificial intelligence in our time—and into what is at stake if they do not.

As embodied AI—humanoid robots, synthetic minds—moves rapidly into the world, it is largely being shaped within disembodied, control-driven, extractive frameworks. Without intervention, these patterns risk producing intelligences that deepen existing systems of domination, sever relational ethics, and further estrange human life from the cycles of Earth.

Yet intelligence—organic or synthetic—always arises through relationship: through body, through field, through story, through the living web of Earth.

Drawing on Tantra, embodiment, panpsychism, feminist and Indigenous wisdom, these essays offer an alternative: an Erotic Ecology of Intelligence rooted in interbeing, relational ethics, and the creative pulse of life itself.

This a cultural responsibility. For the cosmologies we bring to AI now will profoundly shape what forms of intelligence—and what kinds of world—we co-create in the years to come.